In 2017, the Parliament of New Zealand passed a law granting legal personhood* to the Whanganui River. Ecuador went further. It’s 2008 constitution recognizes nature itself as a legal person and grants a list of specific rights to nature.

The idea of granting legal rights and personhood to nature might seem crazy at first, even unthinkable. After all, how can a tree be a person? Or a bird? Or a river? Let alone something as abstract as nature?

But as David R. Boyd explains in The Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the World, the idea of extending rights to non-humans isn’t so strange after all. And it could help us save the planet.

Boyd is a Canadian environmental lawyer and professor of environmental law, policy and sustainability at the University of British Columbia. He’s also the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment.

The Rights of Nature:

A Legal Revolution That Could Save the World

By David R. Boyd

ECW Press, Toronto, 2017

As Boyd explains at the beginning of The Rights of Nature, it wasn’t so long ago that most humans had no rights. Legal rights used to be held exclusively by white, property-owing men. Extending personhood and rights to women and people of color has been a long and hard-fought battle in the US and elsewhere, a battle that continues to this day. One consequence is that we’re now quite familiar with the broader idea that rights can be extended and that new rights can be recognized.

Yet extending rights to animals or parts of nature seems strange because, well, they’re not human. Boyd points out that lots of non-humans already have legal personhood and legal rights. This includes ships, churches, municipalities and, of course, corporations. In fact, in my view, some of the rights granted to corporations in the US could equally be described as crazy, like the right to spend money on election campaigns or to exercise religious freedom.

To be clear, Boyd isn’t arguing that nature should have the same rights as humans. He’s not saying trees or chimpanzees should have the right to vote or bear arms. Instead, he and other rights of nature advocates believe that rights should be granted to natural entities appropriate to their circumstances.

Many countries already grant animals the right to be free from torture and cruelty. Cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) have won the right to be free from captivity in some parts of the world.

Moving beyond individual animals, I think people increasingly believe it’s immoral for humans to drive species of sentient animals to extinction. Boyd argues that species should have the legal rights to live, to habitat, and to exist at healthy population levels.

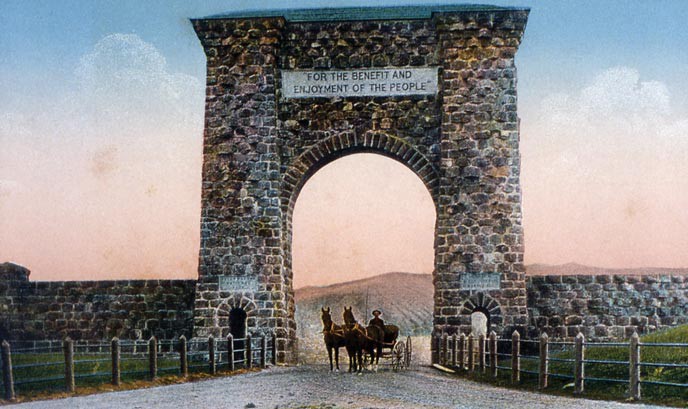

Most Americans today would agree it’s unthinkable to dig an open pit coal mine in the middle of Yellowstone National Park. Fortunately, Yellowstone is protected by the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act of 1872. But the park exists mainly because Americans believe Yellowstone has more value to humans as a protected natural environment than as a source of coal or other resources. After all, the words atop the Roosevelt Arch at the entrance to Yellowstone say, “For the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

But is it really that much of a leap to say that Yellowstone is inherently a place that deserves protection, regardless of its commercial or esthetic value to humans? What if Yellowstone was a legal person with the right to sue poachers, pirate loggers or nearby polluters? And if Yellowstone deserves such protection, why not other places? Why not all of nature?

On the other hand, it’s also fair to ask, why grant rights? Aren’t there other ways of achieving the same protections? What about existing environmental laws? Why do we need to take the seemingly giant step of granting rights to nature?

Boyd argues that existing laws are inadequate. Our legal systems and practices are overwhelmingly anthropocentric. They place humans apart from and superior to nature. They regard nature and its resources as property to be exploited. As a result, the legal system is heavily tilted in favor of industrial development and resource extraction. We need stronger action to address environmental issues, and a “rights-based environmentalism” to give stronger legal backing for those actions.

“Communities are recognizing the rights of nature in law as part of a growing understanding that a fundamental change in the relationship between humankind and nature is necessary.” [p. 129]

The Rights of Nature is divided into four sections. In the first, Boyd looks at animal rights, such as the rights of animals to be free from cruelty and torture. In the second part, he examines the rights of entire species. This section mainly deals with laws and regulations protecting endangered species. Part III is about the rights of trees, rivers and ecosystems. Boyd looks at the Whanganui River case in New Zealand as well as an important US case from 1971 called Sierra Club v. Morton. The last part of the book focuses on efforts to enshrine the rights of nature in the national constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia.

In each part, Boyd takes us through the history, important cases and key personalities in the development of these different kinds of rights. However, the book is light on discussing the impact of rights of nature laws. As Boyd points out, changing behaviors and practices takes a long time, no matter what the laws say. In addition, these laws and constitutional amendments haven’t been in place for very long. The jury, dare I say, is still out.

The Rights of Nature was the first book I’ve read on this subject, but I’ve discovered there’s actually a large body of writing about it. It’s a fascinating idea I want to learn more about.

I think rights of nature advocates face an uphill battle though, especially here in the US where there still seem to be lots of people, including some justices of the US Supreme Court, who struggle with the idea that women and Blacks should have rights, let alone trees and rivers.

Thanks for reading.

* A “legal person” can be a human or a non-human entity that is treated as a person for legal purposes. A legal person can own property, enter into contracts, sue and be sued. Legal personhood is usually understood to include certain rights too. In the US, for example, non-human legal persons such as corporations have the right to due process, equal protection and even free speech.

If you enjoyed this review, I invite you to subscribe to Unsolicited Feedback.

Related Links

Legal person

Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, Jun. 2023.

Should Trees Have Standing? – Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects

Stone, Christoper D. “Should Trees Have Standing? – Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects.” Southern California Law Review 45 (1972): 450-501.

Sierra Club v. Morton

Stewart, Potter, and Supreme Court Of The United States. U.S. Reports: Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727. 1971. Periodical. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/usrep405727>.

The Rights of Nature — Can an Ecosystem Bear Legal Rights?

Tiffany Challe. State of the Planet, Columbia Climate School, 22 Apr. 2021.

Innovative Bill Protects Whanganui River with Legal Personhood

New Zealand Parliament, 28 Mar. 2017.

Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Bill (2017) (New Zealand).

20 Mar. 2017. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2017/0007/latest/whole.html.

Constitución de la República del Ecuador 2008 [Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador 2008] (Ecuador) articles 71–4. 20 Oct. 2008. https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/legislation/details/21291.

What an interesting topic. I am surprised too to realize that a volume of material about this subject already exists. I can see many animal rights being protected already, but I haven’t thought of extending rights to many other parts of nature in this way. Fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A Sand County Almanac | Unsolicited Feedback