The clean energy transition is forcing countries and communities to make some very difficult choices. Weaning ourselves off fossil fuels means we have to ramp up production of electric vehicles, solar panels, wind turbines, transmission lines and batteries. Lots and lots of batteries. And that means we’ll need huge quantities of raw materials: lithium, cobalt, copper, nickel, aluminum and other more exotic critical minerals. We can meet some of the demand for these materials by recycling, but there’s no getting around it, we need more mining.

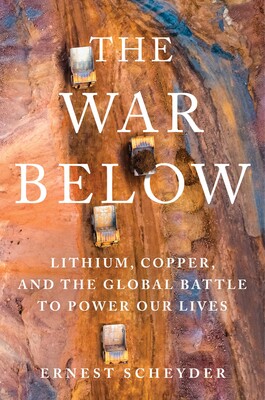

The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives by Ernest Scheyder explores the conflicts and the trade-offs around mining for the materials we need to power the clean energy transition.

The War Below:

Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives

By Ernest Scheyder

Atria/One Signal Publishers, New York, 2024

To illustrate the surging demand for critical minerals, Scheyder lists the materials used to make the battery in an average Tesla Model 3, the most popular electric vehicle (EV) at the time the book was written. Think of this as an ingredient list:

- Lithium – 6 kilograms (kg)

- Nickel – 42 kg

- Cobalt – 8 kg

- Aluminum – 8 kg

- Graphite – 55 kg

- Copper – 17 kg

- Plus more than a mile of copper wiring elsewhere in the motor

Since battery technology is evolving rapidly, these materials and quantities will vary between models and companies over time.

To produce all this material, we need to develop new mines.

“The IEA [International Energy Agency] found that between 2022 and 2030 the world needed to build fifty new lithium mines, sixty new nickel mines and at least seventeen cobalt mines.” [p. 6]

Alright, let’s take a quick survey. Raise your hand if you’d be OK with a lithium mine in your backyard.

Exactly! Now you know what this book is about.

The War Below is a journalistic work. Ernest Scheyder is a senior correspondent for Reuters. He covers the clean energy transition and critical minerals and he’s a graduate of the University of Maine and the Columbia Journalism School. The book is essentially a collection of interwoven stories about mines, mining companies and their impact on surrounding communities and ecosystems. Scheyder goes into great detail about the history of key mining companies and their CEOs, how they’ve been bought, sold and merged into large conglomerates. He covers the activists, families and communities who oppose the mines, and he leads us through seemingly endless legal and political twists and turns in the conflicts about them. There was too much of this detail for me; I couldn’t keep track of all the characters and frankly I wasn’t that interested. Their stories started to get repetitive too.

One case Scheyder describes is the conflict over a proposed lithium mine at Rhyolite Ridge in southern Nevada – one of the largest lithium deposits in the US. Rhyolite Ridge is also home to an endangered species of flowering plant called Tiehm’s buckwheat which thrives in lithium-rich soil. The mine could destroy the plant’s habitat.

The dispute between mining companies and environmentalists at Rhyolite Ridge has been going on for years was still not fully resolved by the time The War Below was published. Scheyder describes several other cases where miners want to extract critical minerals from environmentally sensitive areas or places considered sacred by Indigenous peoples in the US and other countries.

Underlying all these cases is a common question: how do we balance the global need to transition off fossil fuels against the impact that mines or other industrial development will have on local ecosystems and communities? Should a single endangered plant be sufficient cause to block a mine that could help millions transition to clean energy? What about a pristine wilderness area or a sacred site? If no one wants a mine in their backyard how do we protect all our backyards from the effects of climate change?

It’s a question Scheyder never directly addresses in this book.

At the same time, he points out that we can’t expect other countries, especially countries in the global south that have been colonized or exploited in the past, to sacrifice their local environments to satisfy our demand for critical minerals. That’s neither fair nor just.

The international dimensions of this problem are made even more complex by China’s overwhelming dominance in the processing of critical minerals, and America’s desire to achieve some degree of supply chain independence.

Scheyder shows us how mining companies haven’t been especially helpful either, using high pressure tactics to entice landowners to sell their properties, failing to engage early with local governments, not obtaining free, prior and informed consent from Indigenous peoples, and making wildly optimistic forecasts to investors. Scheyder quotes Mark Twain who apparently once said:

“A mine is a hole in the ground owned by a liar.” [p. 47]

Unsolicited Feedback

I think “The War Below” is a stupid title. Can we please stop escalating every disagreement, struggle or conflict into a war. There is no need to militarize normal political debate. It’s unhelpful and increases polarization. More important, as Scheyder clearly shows us throughout this book, any “war” that’s going on is happening above ground, not below, between people who hold opposing views about if, where and how to mine minerals from the earth.

In The War Below, Scheyder tells the stories of some of the people and places caught in the conflict over critical minerals. In doing so he highlights the excruciatingly difficult choices faced by communities and governments. Unfortunately he never directly addresses the question of how these choices should be made. He interviewed dozens of mining executives, scientists, activists and community members for the book, but very few government officials and policymakers. To be fair, Scheyder does call out that US government policy in this area has been unstable – changing from one administration to the next – and schizophrenic with different departments seemingly heading in contradictory directions. But there’s no discussion at all about what principles or guidelines might be used to help make these decisions or shape the decision-making processes. I think this is a major gap in the book.

By the way, there’s some dispute over whether mining for critical materials is better or worse for the environment than producing coal, oil and natural gas. It’s a complicated questions, as this report from the MIT Climate Portal shows, but there’s little doubt mining for critical minerals releases way less CO2 than burning fossil fuels.

Thanks for reading.

Click here for more posts on the environment.

If you enjoyed this review, please subscribe to Unsolicited Feedback.

Related Links

Season 4 of The Big Switch podcast, hosted by Columbia University climate professor Dr. Melissa Lott, focuses on the supply chain for lithium-ion batteries. A couple of episodes related closely to the subject of The War Below.

- Lott, Melissa, host. “The Mining Conundrum for Critical Minerals.” The Big Switch, season 4, episode 2, Columbia SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy, 6. Mar. 2024, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/the-mining-conundrum-for-critical-minerals/.

- Lott, Melissa, host. “The High Stakes for Battery Ingredients.” The Big Switch, season 4, episode 3, Columbia SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy, 13. Mar. 2024, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/the-high-stakes-for-battery-ingredients/.

IEA (2022), Global Supply Chains of EV Batteries, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/global-supply-chains-of-ev-batteries , Licence: CC BY 4.0

Timperley, Jocelyn. “Explainer: These six metals are key to a low-carbon future.” Carbon Brief, 12 Apr. 2018, https://www.carbonbrief.org/explainer-these-six-metals-are-key-to-a-low-carbon-future/.

Wow…and here is a whole other area that I am totally clueless about! I’m so glad you review this genre of books for us because I learn things even if I don’t end up reading the book myself. We are currently watching a small town near us trying to keep a rock quarry from coming in and disrupting their whole community. Finding the right balance between the impacts of development and the benefits of them is complex indeed.

I so agree with you about the title; I would prefer less hostile language too. I grew up in a heritage that used military language to spur us on to “good works,” but as an adult I find it troubling and am spending years trying to discard it. I’m sure there is a lot of it still so deeply embedded in me that I haven’t uncovered it yet. I’ll have to keep mining for it. (See what I did there? lol)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree – finding the right balance is so difficult.

And drilling into our use of language seems to be an ongoing battle, oops I mean struggle. 🙂

LikeLike

While I was reading your review, I thought “This is a timely topic, but I think I would feel a bit overwhelmingly helpless if I delved into it.” And then you described that the author doesn’t explore how better decisions might be made in this area. Well! That would not help alleviate my feelings of helplessness, haha. It’s a self-centered view, but it is what it is. Thanks for the related links – I’ll check out some of those instead.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Feeling helpless is a perfectly reasonable reaction here 🙂. Balancing all the competing interests in a way that’s constructive and in line with climate science is mind- bogglingly complicated. I hope you enjoy the other links.

LikeLiked by 1 person