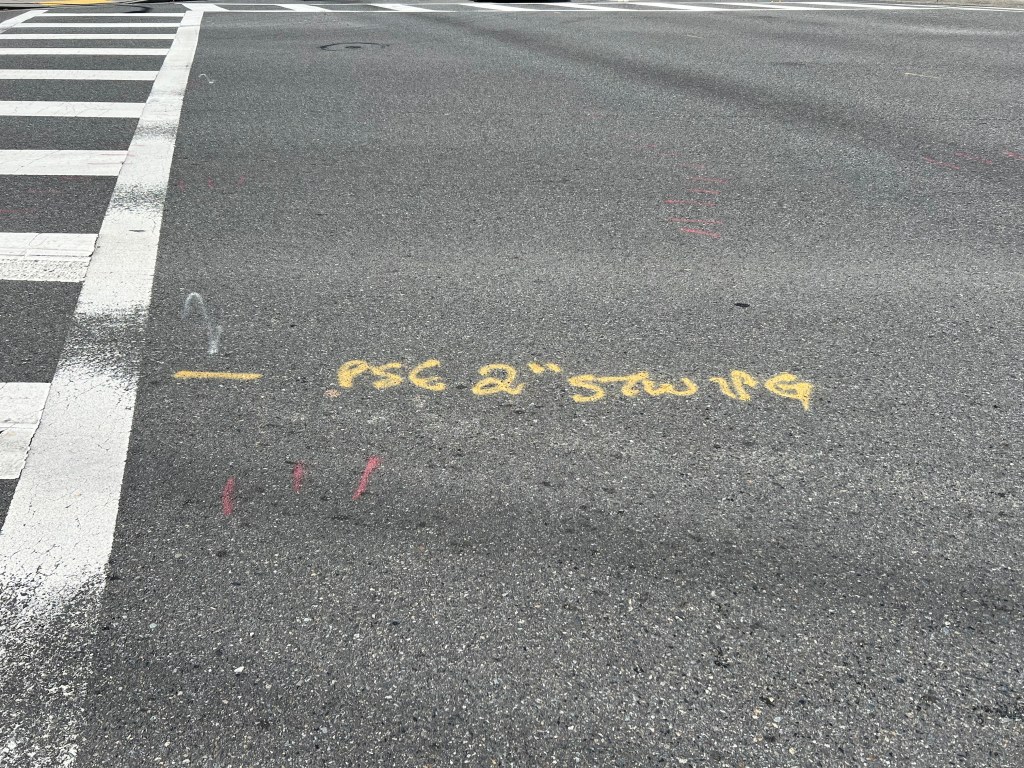

If your city or town is anything like mine, you’ve probably seen lots of strange markings scrawled all over the place. It’s not graffiti, although there could be plenty of that too. I’m talking about those cryptic notations spray-painted in bright colors on streets and sidewalks. These marks hint at something hidden and buried.

OK, they’re not exactly a great mystery. They indicate the location of pipes for water, sewage and natural gas, and cables for electricity, telephone and internet – the infrastructure we depend on to keep our civilization running safely, efficiently and comfortably.

On second thought, all that infrastructure really is kind of mysterious. Partly because most of it is hidden and buried, and partly because it’s so incredibly complex.

How Infrastructure Works: Inside the Systems That Shape Our World is a wonderful book that looks deeply at the function, development and future of infrastructure. It’s written by Deb Chachra, a Professor of Engineering at Olin College near Boston. Chachra holds a PhD in Materials Science from the University of Toronto. She works and writes on themes at the intersection of technology and society, which is exactly where infrastructure lies.

How Infrastructure Works:

Inside the Systems That Shape Our World

By Deb Chachra

Riverhead Books, New York, 2023

The main message of this book is that infrastructure is so much more than just pipes and cables, more than what Chachra calls “charismatic megastructures” like airports, dams and power plants. It is also fundamentally social and political.

Infrastructure, she writes, is how we care for each other.

What does infrastructure do?

How Infrastructure Works is not a technical book. It doesn’t tell you how the internet or sewage treatment plants work. Instead, it’s about what infrastructure does. In Chachra’s view, infrastructure brings energy and resources to where we want to use them, to where our bodies are. In so doing, infrastructure gives us agency and power.

Infrastructure empowers us in unprecedented ways by delivering electricity, water, light, heat, mechanical labor, wastewater disposal, transportation and information, all with minimal time and physical effort. Infrastructure, Chachra says, has been especially beneficial to women who often had to perform (and still perform) gendered labor like fetching water and firewood, cooking and cleaning.

Infrastructure both consumes and delivers enormous amounts of energy, mainly from burning fossil fuels. Energy makes infrastructure possible, and infrastructure makes energy cheaper and more abundant.

“Energy usage has come at tremendous cost, with impacts that are still unfolding. But at the same time, infrastructural systems have provided access to energy and so enabled historically unprecedented levels of agency to more people, especially women.” [p. 40]

Today, we rely on infrastructure to accomplish virtually everything we do, from travelling around the world to mundane household chores.

“The washing machine I use for my clothes needs not only electricity but also a supply of clean water. Some of that water comes from a hot-water heater, which itself relies on a piped-in supply of natural gas, and the dirty water drains into a sewage line. Four different infrastructural systems converge when I do my laundry.” [p. 11]

However, that dependence means we’re vulnerable when infrastructure fails, as it is now starting to do more frequently.

Collective megastructures

Infrastructure is created to serve whole communities, up to and including the entire world. Chachra emphasizes that building and maintaining infrastructure requires deep collaboration by many people across space and time.

In other words, infrastructural systems are collective systems. They embody collective decisions about how people in a particular space and community have decided to meet their common needs. Building and maintaining them is an act of caring, Chachra says, for each other and for future generations too. It’s caring at scale.

Although infrastructural systems are technological systems, rooted in the physical world, they are built collectively by groups of people doing something as simple as digging a ditch to channel water, or as complex as launching satellites into orbit for the Global Positioning System.

“This is a societal shift that’s hiding in plain sight: most technological systems, including mass-produced material goods, are now products of collective, rather than individual, intelligence. As a general rule, if it didn’t already exist about a hundred years ago, it’s not something that a single person could fully understand or create today. The fabric of daily life is created from technologies that have outpaced our ability as individuals to fully understand or recreate them.” [p. 78]

These systems are layered on top of each other, recursively, resulting in incredible complexity.

“The brain-exploding insight, the one that we all live with whether we acknowledge it or not, is this: for a large fraction of humanity, the ways we meet our most basic needs, the ways we carry out the most mundane and quotidian activities of our daily lives, and the material culture in which we are embedded are all beyond our capacity to comprehend or even fully apprehend.” [p. 84]

This is all very recent, Chachra points out. Roads and aqueducts are our oldest infrastructure, dating back to ancient Rome or earlier. But most of the infrastructure we rely on today was developed following the Industrial Revolution. And the three truly globe-spanning infrastructural systems – telecommunication networks, aviation and containerized shipping – are all less than 50 years old.

A steep price

All this infrastructure has come at a steep price. It may bring benefits to many, but privately owned infrastructure delivers profits to just a few. Infrastructure development has displaced underrepresented people, especially people of color. US highways were often built through Black neighborhoods. Dams and reservoirs have inundated Native American lands. Most of all, by burning fossil fuels to generate electricity, move people and goods, and heat water and buildings, infrastructure has been a main driver of climate change.

Chachra points out a vicious circle here: Infrastructure is driving climate change, and climate change increasingly threatens infrastructure. Because the upfront costs and development time of infrastructure are so large, and its planned lifespan so long, infrastructure depends upon a stable environment. Extreme weather, like the Texas winter storm of 2021, is frequently causing conditions that approach and even exceed the design specifications of our infrastructural systems.

Erica Gies makes a similar point in her book Water Always Wins. She notes that large “grey infrastructure” projects, those made with lots of concrete, are engineered and built based on specific assumptions about the environment. With climate change, those assumptions may not be valid by the time the project is completed, let alone over its useful life.

Opportunity in abundance

Chachra says we now have both an opportunity and an obligation to recreate infrastructure to be functional, sustainable, resilient, and equitable. These four qualities are inextricable, she argues.

“For all the limitations and the inequality baked into them, our infrastructural systems remain an important means to reduce human suffering and to increase agency. It is absolutely possible to create systems that are functional, resilient, sustainable, and equitable, on a global scale. The challenge is figuring out how to get from here to there, technologically and socially.” [p. 200]

She’s optimistic about the possibilities for new infrastructure based on renewable energy. Renewable energy is both limitless and cheap. This could allow us to transition from an economy based on scarcity to one based on abundance.

“We’re accustomed to thinking about making the transition away from fossil fuels to renewable sources as one that we are doing under duress, making a sacrifice to stave off disaster. But that’s not what we’re doing. What we’re doing is leveling up. We—you, me, anyone who is alive today—we have the opportunity to not just live through but contribute to a species-wide transition from struggle to security, from scarcity to abundance. We can be the best possible ancestors to future generations, putting them on a permanent, sustainable path of abundance and thriving. And we can do it for all of our descendants—all of humanity—not just a narrow line.” [p. 238]

This collective nature of infrastructure leads Chachra to the idea of “infrastructural citizenship.”

“This idea of being in an ongoing relationship with others simply by virtue of having bodies that exist in the world and which share common needs is what I think of as ‘infrastructural citizenship.’ It’s a citizenship that encompasses the people who are in a particular place in the world or connected by networks today, as well as those yet to come. It carries with it the responsibility to sustainably steward common-pool resources, including the environment itself, so that future communities can support themselves and each other so they all can thrive. Infrastructural citizenship is not just care at scale, but care in perpetuity.” [p. 276]

Unsolicited Feedback

Many years ago, I was chatting with a friend and we somehow got onto the topic of infrastructure. (I’m a nerd. I admit it.) I observed that our civilization has built up layer upon layer of infrastructure. We get enormous benefits from it, but we’ve become completely dependent on it too. Few of us know how to light a fire, weave cloth or grow enough food to feed our families, let alone purify water or generate our own electricity. This makes us extremely vulnerable when infrastructure fails.

So imagine my delight when this book not only echoed my long-ago musings but broadened my understanding immensely.

Until now, I’ve always thought of infrastructure as a product of technology. Chachra’s framing of infrastructure as the way we care for each other and for future generations was jarring at first. I thought the idea might be a little rosy too. I mean infrastructure costs billions of dollars to build, and it wouldn’t get built unless some people benefited financially. But after finishing this book, I think it’s a compelling idea. It’s a bigger, broader perspective that encourages us to think about who infrastructure is for, the environment in which it is situated, and the kind of world we want to build together.

How Infrastructure Works is one of those books that helps you see an important part of the world from a revealing new angle. It might seem like a nerdy topic, but it’s rewarding and worthwhile.

Thanks for reading.

If you enjoyed this review, please subscribe to Unsolicited Feedback.

Related Links

Chachra, Deb. “Debbie Chachra – How Infrastructure Works | The Conference 2023.” YouTube, 22 Sep. 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oK6BRwwhgbo.

Discover more from Unsolicited Feedback

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Ooh, this looks fascinating, thank you for highlighting it (I know I’m a bit behind with my blog reading!). I’m going to suggest this to my best friend as a book to read together, but am putting it on my own wishlist too anyway!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you enjoy it!

LikeLike

Pingback: Nonfiction November 2024 Week 2: Choosing Nonfiction | Unsolicited Feedback