For the past 10,000 years, Earth’s climate has been remarkably stable. Average global temperatures have fluctuated in a narrow range of about 1 degree Celsius. Human civilization – agriculture, writing, metallurgy, government, cat videos, all of it, good and bad – emerged during this favorable period known as the Holocene.

But the stable climate of the Holocene is very unusual. Over Earth’s 4.5-billion year history, the climate has varied wildly, from an extremely cold Snowball Earth covered in ice from the poles to the tropics, to an uncomfortably warm Hothouse Earth where palm trees grew in the Arctic, and everything in between.

What can we learn from past episodes of climate change to help us deal with today’s climate crisis? That’s the question Michael Mann sets out to answer in his latest book Our Fragile Moment: How Lessons from Earth’s Past Can Help Us Survive the Climate Crisis.

Our Fragile Moment:

How Lessons from Earth’s Past

Can Help Us Survive the Climate Crisis

By Michael E. Mann

PublicAffairs, New York, 2023

Michael E. Mann is a Presidential Distinguished Professor of Earth & Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania and the director of the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media (PCSSM). Mann has written several books, but he’s probably best known for the “hockey stick” graph which he and a couple of colleagues produced while he was a PhD student.

The Hockey Stick Graph

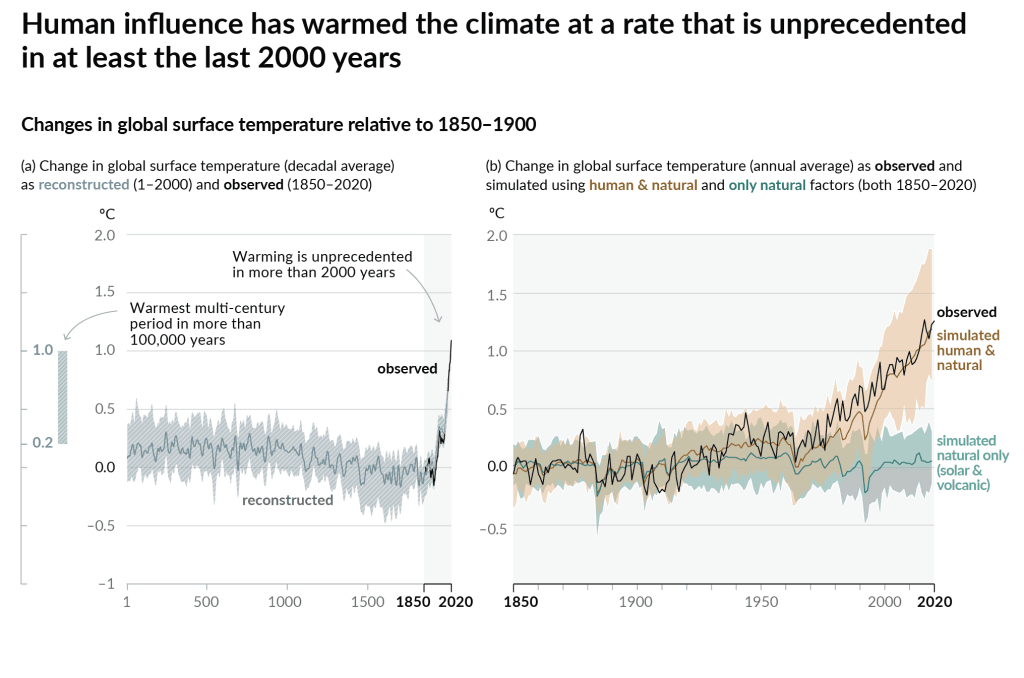

First published in 1999, the hockey stick graph charts the changes in Earth’s global average surface temperature for the past two thousand years. Here’s an updated version in panel (a) from a 2021 IPCC report.

As you can see, temperatures were relatively flat, and even declining a little, up until the late 1800’s. Since then, global temperatures have risen sharply like the blade of a hockey stick. The graph has long been controversial. Most scientists agree the steep rise is due to human activity, mainly burning fossil fuels, while skeptics claim the changes are due to natural fluctuations in Earth’s climate.

Earlier this year, Mann won a $1-million judgement in a defamation lawsuit against two conservative bloggers who accused him of manipulating the hockey stick data and compared him to a child molester.

For another very readable version of the hockey stick graph, see Randall Munroe’s wonderful drawing on XKCD. Andrew Dessler extends the graph into the future in an article on his substack The Climate Brink.

Resilient … up to a Point

The hockey stick graph illustrates one of the main themes of Our Fragile Moment: Earth’s climate system is resilient, but it can also be pushed into radically new states. By examining some of the most consequential episodes of climate change in Earth’s long history, Mann shows us that the Holocene really is a fragile moment.

In each chapter, Mann looks at an example of past climate change, diving deep into the science of how the climate system works, why it went haywire and the lessons we can learn.

One recurring cause he explores is runaway feedback loops. Take the ice-albedo feedback loop for example. Albedo measures the fraction of light that gets reflected off the surface of an object like a planet or moon. White ice at the poles has a high albedo: it reflects a lot of sunlight back into space helping to cool the Earth. As the climate warms, some of the ice melts, leaving behind darker open water which reflects less sunlight. Less reflection, more warming, more melting ice, less reflection, more warming and so on. The ice-albedo feedback loop works in the opposite direction too when the climate is cooling, leading in the extreme case to Snowball Earth. This is an example of a positive feedback loop that reinforces and even accelerates climate change.

By pumping enormous amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, we risk triggering a runaway ice-albedo feedback effect. One possible outcome scientists worry about is the collapse of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets leading to rising sea levels and coastal flooding. It’s starting to happen already.

This highlights another aspect of our climate system: tipping points. Most climate change has been gradual, taking place over millions of years. But sometimes change can happen much more quickly. Until humans came along, “much more quickly” still meant tens of thousands of years. Now it’s mere decades. A tipping point refers to one of these sudden changes like the collapse of the polar ice sheets.

“These systems are nonlinear, and they exhibit tipping point behavior – behavior that is irreversible on human timescales. And because of the nature of scientific uncertainty, we don’t know precisely how close we are to these tipping points. That fact should give us pause as we continue to recklessly warm our planet with carbon pollution.” [p. 64-65]

For the past 200 years, Mann warns, we’ve been running an “unprecedented and uncontrolled” experiment on our planet. We’ve been burning fossil carbon, laid down in the Earth’s crust millions of years ago, and releasing over a trillion metric tons of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere.[2] The resulting warming threatens to destabilize Earth’s climate, kicking us out of the Holocene and ending this fragile moment.

Scientists and Their Methods

A second theme of Our Fragile Moment is about how scientists do their work. Paleoclimatology, the study of ancient climates, is particularly difficult because we don’t have precise data about Earth’s climate millions and billions of years ago. We must make careful inferences from sources like ice cores and rock samples. As a result, scientists say things like, “the data suggests …” or “the evidence supports …” They often attach probabilities or likelihoods to any conclusions they reach. This can be frustrating for those of us who want definite answers and greater certainty, but as Mann says repeatedly, that’s not how science works.

One example that Mann details is the attempt to estimate Earth’s equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS). ECS is “… how much warming you get if you double the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere.” CO2 concentration has risen from 280 parts per million (ppm) in pre-industrial times to about 425 ppm today[3] – not quite a doubling yet but that’s where we’re heading unless we take dramatic action. If we knew how sensitive the climate is to increased CO2 concentration, we’d be able to predict the effects more precisely. It turns out that ECS is difficult to pin down due to the complexities of the climate system. The current best estimate, according to Mann, is somewhere in the range of 2.3°C – 4.5°C with 3°C being the most likely value. As our models and our understanding have improved, this range has narrowed and scientists have become more confident in its accuracy, but uncertainty remains.

As Mann says, “uncertainty is not our friend.” Because models are incomplete and imperfect, scientists must be cautious in their conclusions. It’s likely that models understate risks and understate likely impacts. For example, Mann discusses how current climate models do not explain the collapse of the Anasazi civilization in the US Southwest around 1300 CE even though we know this happened due to crop failures caused by an increasingly dry local climate.

“It’s possible that we are underestimating the fragility of civilization when subject to climate-driven stresses. That our best modeling efforts seem to underpredict the potential for societal collapse, in this key test case when we know precisely when it occurred, should give us pause when it comes to the unprecedented and uncontrolled planetary experiment we are now running.” [p. 40]

Unsolicited Feedback

Our Fragile Moment is densely packed with scientific information. Mann explains it all in a way that’s easy to understand, but there is a lot to absorb and I found it a little heavy going in places. It helped that I had read Andrew Dessler’s excellent climate science textbook Introduction to Modern Climate Change last year. In fact, if you’re not up for tackling a full textbook, then Our Fragile Moment will give you a pretty good grounding in climate science. The book overlaps quite a bit with Peter Brannen’s The Ends of the World about Earth’s five great mass extinctions. Brannen is a more engaging writer, but he’s a journalist. Mann is a scientist.

I think the book also gives valuable insights into how scientists do their work and why they never seem to be as clear and unequivocal as we might like.

So what lessons does Mann think we can learn from past changes in Earth’s climate?

Here I found the book a little disappointing. Each of the episodes Mann examines is both similar and different to our circumstances today. Since there aren’t any exact comparisons, science can provide suggestions and indications but not certainty. Mann provides little specific guidance. Still I learned some valuable lessons.

First, Earth’s climate has varied wildly over its history, but the conditions that support human life and human civilization are rare and narrow.

“Climate variability has at times created new niches that humans or their ancestors could potentially exploit, and challenges that caused devastation, then spurred innovation. But the conditions that allowed humans to live on this Earth are incredibly fragile, and there’s a relatively narrow envelope of climate variability within which human civilization remains viable.” [p. 3]

Earth’s climate can change fairly quickly, normally on geologic timescales, but we’ve accelerated everything.

Our understanding of the climate system is improving, and our models are getting more precise. However, they most likely still understate the potential impacts and threats of climate change.

Due to the tipping point behavior of the climate system, uncertainty is not our friend. Yet Mann cautions that uncertainty is no excuse for either inaction or doom.

“Evidence supports neither fatalism nor complacency.” [p. 232]

Climate change is happening now. If we miss the UN’s 1.5°C target for global warming, which seems very likely, that’s no reason to give up or stop acting. Mann uses highway off ramps as an analogy that I really like. To minimize the effects of climate change we must get off the global warming highway as soon as possible. If we miss the 1.5°C off ramp we must work hard to take the next off ramp or the earliest possible one after that. Every tenth of a degree matters.

When the giant Chicxulub meteor slammed into Earth 65 million years ago, the dinosaurs didn’t see it coming and couldn’t have done anything about it anyway. We are not dinosaurs. We can see what’s coming, and we can do something about it. We have both urgency and agency. I think that’s the most important lesson from Our Fragile Moment.

Thanks for reading.

Click here for more posts on climate change.

If you enjoyed this review, please subscribe to Unsolicited Feedback.

References

[1] IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001. Figure SPM.1, p. 6.

[2] Global Carbon Budget (2023) – with major processing by Our World in Data. “Cumulative CO₂ emissions – GCB” [dataset]. Global Carbon Project, “Global Carbon Budget” [original data]. Retrieved May 16, 2024 from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cumulative-co-emissions.

[3] “Carbon dioxide now more than 50% higher than pre-industrial levels.” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 3 Jun. 2022, https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/carbon-dioxide-now-more-than-50-higher-than-pre-industrial-levels.

Related Links

Dessler, Andrew. “The scariest climate plot in the world.” The Climate Brink, 14 Nov. 2023, https://www.theclimatebrink.com/p/the-scariest-climate-plot-in-the.

King, Pamela. “Embattled Climate Scientist Michael Mann Wins $1 Million in Defamation Lawsuit.” Scientific American, 8 Feb. 2024, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/embattled-climate-scientist-michael-mann-wins-1-million-in-defamation-lawsuit.

Moore, Randall. “Earth Temperature Timeline.” XKCD, No. 1732, https://xkcd.com/1732/.

The Keeling Curve

Measuring atmospheric concentrations of CO₂ at the Mauna Loa Observatory since 1958. See videos for a quick history.

Discover more from Unsolicited Feedback

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This sounds like another book I should put on my reading list. I appreciate your bottom line from it: “We are not dinosaurs. We can see what’s coming, and we can do something about it. We have both urgency and agency. I think that’s the most important lesson from Our Fragile Moment.” Thanks for such clear reviews on difficult topics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Our Fragile Moment | tim's eco news🌎

Pingback: Utah and Four Corners Road Trip 2025 | Unsolicited Feedback