Dr. Fei-Fei Li may not be a household name, but for over twenty years she’s been a driving force behind the advancement of artificial intelligence, particularly computer vision and deep learning. Her book, The Worlds I See: Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI, is both a personal memoir and a history of AI.

Li is a professor of computer science at Stanford University with over 300 scientific publications to her name. From 2013 to 2018, she was the Director of Stanford’s AI Lab (SAIL). She also co-founded AI4ALL, “a nonprofit dedicated to increasing diversity and inclusion in AI education, research, development, and policy.”

The Worlds I See:

Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI

By Fei-Fei Li

Flatiron Books, New York, 2023

Li was born in Beijing in 1976. She immigrated to the US in 1991 just in time to start high school in Parsippany, New Jersey. Her immigrant experience is central to her life and to the book. She recounts her family’s difficult transition from a relatively comfortable middle-class life in China to poverty in America, “consigned to a permanent state of vulnerability” while struggling to learn English and caring for her chronically ill mother without health insurance.

She also writes about her journey as a researcher and scientist, starting with her love of physics and mathematics. Her high school math teacher played an enormous supporting role throughout her life, and the two families have formed a bond that spans generations. She won a scholarship to attend Princeton for her undergraduate studies and earned her PhD at the California Institute of Technology.

In the field of AI, Li is best known as the creator of ImageNet. First released in 2009, ImageNet is a database of about 14 million images grouped into over 20,000 categories and available for free to AI researchers. Assembling, organizing and labeling all these images was a herculean multi-year effort and a daring career bet. Many of Li’s colleagues told her the project was a waste of time. But from her early research in neuroscience where she studied people’s ability to recognize images in a tiny fraction of a second, she formed the intuition that the human brain is wired in a fundamental way to recognize categories of things. For example, you can instantly tell that an animal you see in the park is a dog even if you’ve never seen one of that breed before.

“The ability to categorize empowers us to a degree that’s hard to overstate. Rather than bury us in the innumerable details of light, color and form, vision turns our world into the kind of discrete concepts we can describe with words — useful ideas, arrayed around us like a map, reducing a complex reality to something we can understand at a glance and react to within a moment’s time. It’s how our ancient ancestors survived an environment of pure chaos, how generations of artists extracted beauty and meaning from everyday life, and how, even today, we continue to find our way around a world defined by ever-growing complexity.” [p. 127]

Li believed that computer vision would likewise need the ability to recognize categories of objects. She realized that a crucial prerequisite was data, specifically large sets of categorized images that could be used to train machine-learned image recognition models.

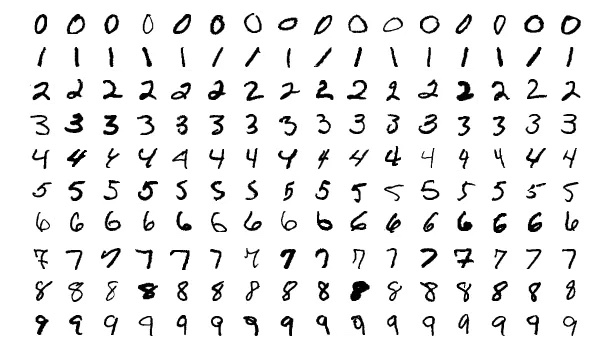

Back in 1992, computer scientist Yann LeCun and his colleagues had successfully trained a neural network (a type of machine-learned model) to recognize handwritten digits in ZIP codes for the US Post Office. In hindsight, that turned out to be a relatively simple problem. Even though there’s wide variation in human handwriting, as you can see in the picture below, the model still had to recognize only ten things, the digits 0 – 9.

Generalizing this capability to recognize any type of object is a much tougher problem. Early neural networks weren’t up to the task and they fell out of favor for over a decade. One reason was they didn’t have enough data to train on. This was the gap Fei-Fei Li and her students filled with ImageNet. It enabled other computer scientists like Geoffrey Hinton and his colleagues at the University of Toronto to make huge leaps in image recognition accuracy using convolutional neural networks, It was not only a vindication for Li and ImageNet, but also for Hinton and neural networks. It bore,

“… the hallmark of every great breakthrough: the veneer of lunacy wrapped around an idea that just might make sense.” [p. 202]

(Aside: Over the years I’ve often been tickled by the bizarre-sounding names given to machine learning algorithms like support vector machines, maximum entropy and boosted trees.)

The success of deep neural networks, backed by large datasets like ImageNet, helped launch the incredible advances in artificial intelligence capabilities we’re seeing today.

Li covers this history and the part she played in some depth. Although the style of writing is a little formal, she explains the concepts clearly with enough geeky detail to be interesting but not overwhelming. The cast of characters she’s worked with over the years is a Who’s Who of the AI field.

She also writes about some important transitions in AI that have begun in recent years. I found this to be one of the most interesting aspects of The Worlds I See. First, leadership in AI research – at least research on algorithms — has largely moved from universities to corporations. That’s because private corporations possess the world’s largest datasets, like Google’s search history, or Facebook’s social graph. To put this in perspective, it took Li and her team several years to complete ImageNet with roughly 14 million images. Well nowadays, people upload 95 million images to Instagram every day. (I used to work at Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram.) This data is private, proprietary and closely guarded. Storing it and processing it requires massive data centers that are beyond the resources of any university.

And this leads to the other trend that Li discusses in her book: a new focus on AI ethics, sometimes known as responsible AI. How much data are these companies keeping about each of us? Do we really want research in fundamental capabilities like artificial intelligence to be the exclusive property of corporations? How do we ensure AI models aren’t biased against minorities or historically disadvantaged or under-represented communities? What kind of harms could AI systems cause and how do we protect ourselves against them? Erica Thompson focuses on these issues too in her book Escape from Model Land.

So it was no surprise that Li co-founded Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI, or that as the book concludes, she’s spending more of her time on policy matters including testifying before the US Congress.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence are truly astonishing. We’re seeing and experiencing a revolution in real time. AI’s impacts on society are impossible to fully predict, but they will be transformative. The Worlds I See is a great read for anyone interested in the history of artificial intelligence.

It’s also the story of an immigrant’s struggle for belonging and purpose in a new country. I’m an immigrant myself, but I came from Canada. I moved from one democratic, capitalist, majority white, predominantly English-speaking, drive-on-the-right-hand-side-of-the-road, Starbucks-on-every-corner country to another. My immigrant journey was trivially easy compared to Li and most other immigrants. Throughout my career, I’ve had the privilege of working with people who immigrated to the US from all over the world. I’ve always admired their courage and drive, but except for a few close friends, I’ve not always appreciated the full depth of their challenges and the strength and tenacity needed to overcome them. That’s perhaps the most moving part of The Worlds I See.

Thanks for reading.

If you enjoyed this review, please subscribe to Unsolicited Feedback.

Discover more from Unsolicited Feedback

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This sounds like another book that is very relevant to our times. I’ll see if my library has it!

LikeLiked by 1 person