I used to travel regularly to the Cascade Mountains in Washington State. On spring and summer evenings, sitting around a campfire or relaxing at a cabin in the woods, I’d sometimes hear owls hooting. Occasionally I’d catch a shadowy glimpse of one swooping silently from tree to tree. These encounters were thrilling and at the same time a little spooky.

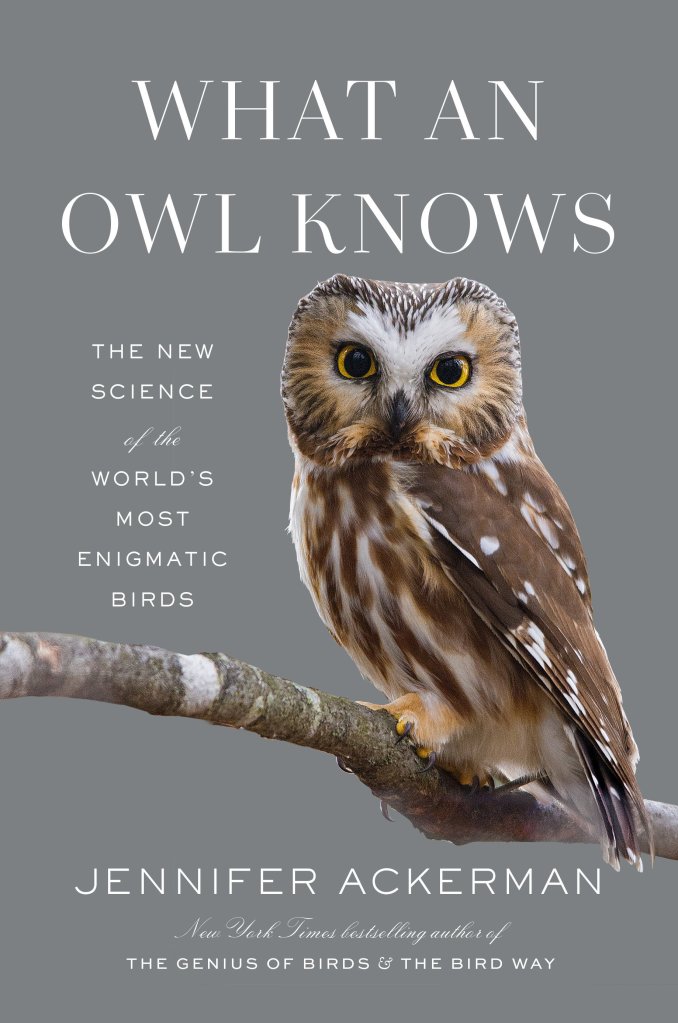

According to Jennifer Ackerman, author of What an Owl Knows: The New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds, my mixed feelings about owls are shared by, well, most of humanity.

Jennifer Ackerman is a science, nature and health writer with a BA in English from Yale University. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, and National Geographic. What an Owl Knows is her seventh book and her fourth about birds.

In this book, Ackerman surveys the latest research about owls, the scientists who study them, and the ways we humans relate to them.

What an Owl Knows:

The New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds

By Jennifer Ackerman

Penguin Press, New York, 2023

Humans have always been fascinated by owls. Ackerman suggests it might be because their upright bodies, round faces and large forward-facing eyes make them look a little like us, at least more like us than any other bird.

Owls appeared in cave paintings in southern France 36,000 years ago. They figure in Greek and Roman mythology as symbols of knowledge, wisdom and judgement. Hedwig, the famous Snowy Owl from J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter stories, is a reliable messenger and loyal companion. More recently, New Yorkers were captivated by the feisty independence of Falco, a Eurasian Eagle Owl who escaped from the Central Park Zoo. Despite a lifetime in captivity, Falco learned to hunt and fend for himself, surviving for over a year in Central Park until his untimely death.

Yet they’re also mysterious, hunting at night, hooting and shrieking in the dark, and so superbly camouflaged that they’re practically invisible by day. Plus, they can swivel their heads 180 degrees to look directly behind them. Creepy! As Ackerman tells us, in some cultures owls are feared as omens of death.

I found the chapter on owl physiology to be the most interesting, particularly the unique characteristics that make them such formidable hunters. Those large forward-facing eyes give owls excellent binocular night vision. They can even see into the ultraviolet. Owls have superb hearing too. Their round facial disk is composed of special feathers that direct sounds to the owl’s ears, like a built-in radar dish. Owls can use muscles at the base of these feathers to adjust the shape of the disk, fine-tuning what they hear. Many species have asymmetrically positioned ears to better help them locate their prey. With all these adaptations, they can hear the movement of mice and voles under a foot and a half of snow. Their wings and feathers are highly evolved for silent, stealthy flight including tiny bristles on the leading edges of their wings that help dampen the sounds of their movement. Finally, owls have powerful feet with flexible talons that can form an X-shaped grip on their prey.

It’s no wonder they’re sometimes called “wolves of the sky.”

https://www.birdcount.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/eastern-screech-owl-isaac-polanski-michigan-615090804-1.33-1280×960.jpg

But there’s still a lot we don’t know about owls.

To begin with, we don’t know how many there are. They’re found on every continent except Antarctica, but because they’re nocturnal, it’s very difficult to get accurate population estimates. We’re not even sure how many species of owls exist. Ackerman says there are about 260 known species, but that number is growing as more are discovered and as DNA analysis helps scientists tease apart multiple species from existing ones.

We’re only starting to learn about their migration patterns. Advances in tracking tags and geolocation transmitters are finally helping us learn more. I was familiar with some of these developments from reading World on a Wing by Scott Weidensaul. In fact Weidensaul appears prominently in Ackerman’s chapter on owl migration.

Throughout the book Ackerman introduces us to the many scientists and researchers, some of them volunteers, who study owls. There was a little too much of this for my taste. For example, the chapter on owl hooting and vocalization seemed to be at least as much about the humans as the owls.

What an Owl Knows contains less discussion than I expected about humanity’s impact on owls. Ackerman mostly saves this topic for an afterword titled “Saving Owls.” Habitat loss and deforestation are their greatest threats. Climate change is affecting them too, of course, particularly the migratory species where a warming climate is affecting the lifecycle timing and abundance of their prey. She notes that the generalists, the ones with flexible diets and wide habitat ranges seem to be adapting and even thriving. But not all species are so fortunate.

“The losers in the drama of evolution and extinction will likely be the specialists limited to narrow ecological niches and small geographic ranges, island species, forest-dependent species, and those that have lost most of their habitats.” [p. 274]

Thor Hansen makes a similar point about climate change favoring generalist species in his excellent book Hurricane Lizards and Plastic Squid.

Ackerman’s writing is clear and straightforward. But while I learned lots of interesting facts about owls from What an Owl Knows, I found it hard to pull out more general themes or messages. Overall, it left me a little unsatisfied. Other nature books I’ve read, like Weidensaul’s World on a Wing and Hansen’s Hurricane Lizards and Plastic Squid do a better job of this. Perhaps it’s because, as Ackerman says, owls vary so widely in size, appearance and behavior making it difficult to form more general observations. Similarly she doesn’t use owls as a jumping off point for more poetic or philosophical explorations like Lyanda Lynn Haupt does in her books Crow Planet and Mozart’s Starling.

That said, I did like how Ackerman wrapped up the last chapter of the book by saying owls “enchant the landscape” and “remind us that we’re always perched on the edge of mystery.”

They certainly do.

Thanks for reading.

If you enjoyed this review, please subscribe to Unsolicited Feedback.

Related Links

To Catch Voles Under The Snow, Great Gray Owls Must Overcome An Acoustic Mirage

Rebecca Heisman. All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 4 Jan. 2024.

Discover more from Unsolicited Feedback

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.