Introduction to Modern Climate Change is a college level textbook aimed at both science and non-science majors. Don’t let that put you off. Anyone with basic high school algebra and chemistry can read this book and learn an incredible amount. I certainly did.

The author is Andrew E. Dessler, Professor of Atmospheric Sciences and director of Texas A&M University’s Texas Center for Climate Studies.

The first half of the book covers the science of climate change. The second half looks at the impacts of climate change and the policies needed to address it.

Introduction to Modern Climate Change, 3rd Edition

By Andrew E. Dessler

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2022

The Science of Climate Change

To understand if our climate is changing, why it’s changing and how, we first need to understand how climate works.

As Mark Twain famously said:

“Climate is what you expect; weather is what you get.”

In other words, weather is a snapshot of the state of the atmosphere at a particular moment, while climate is a statistical description of the weather over a period of time, usually decades or longer.

In the first half of the book Dessler builds a simple model of Earth’s climate and then uses it to explore the causes and impacts of climate change.

It begins with the sun.

Dessler explains that the Earth, like any other object, exists in an energy balance. Energy input (sunlight) must equal energy output (reflected light and heat, also known as blackbody radiation). If there’s an increase in energy input – suppose the sun gets brighter for some reason – then the planet will heat up until energy output is once again in balance. If the energy reaching the Earth is reduced, then the planet will cool until a new equilibrium is reached.

It’s just like a pot of water on your stove.

Except heating and cooling the planet takes a lot longer: thousands, sometimes tens of thousands of years.

This idea of energy balance forms the crux of Dessler’s climate model. He explains concepts like albedo, blackbody radiation, the carbon cycle, radiative forcing, feedback loops, climate sensitivity, and how each one affects Earth’s energy balance. I learned none of this in school – admittedly school was a long time ago for me – so this part of the book gave a huge boost to my understanding of climate.

He shows how energy input coming from the sun gets absorbed and reflected in a complex interplay between Earth’s atmosphere, land and oceans leading over time to an equilibrium temperature for the planet.

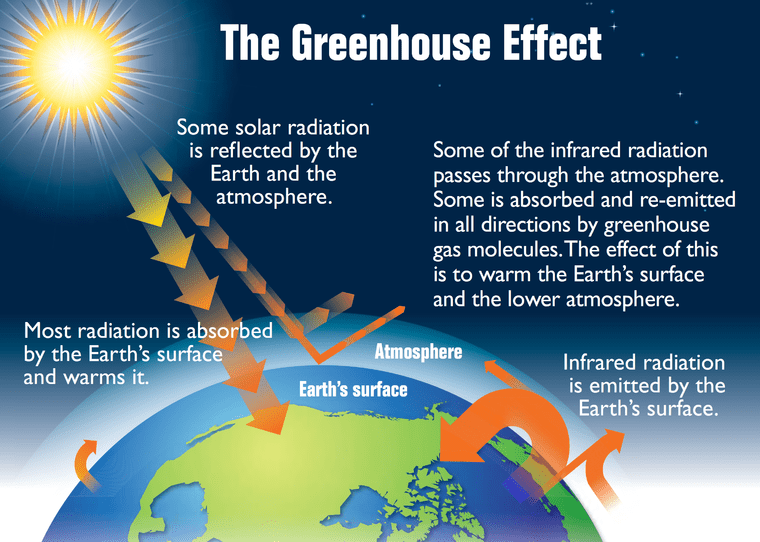

One key aspect of this interplay is the greenhouse effect. Greenhouse gasses (GHGs) in the atmosphere, like carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), absorb some of the sun’s energy, preventing it from escaping back into space (i.e. reducing Earth’s energy output) and thereby warming the planet. This is a good thing. Without the warming effect of the atmosphere, the average surface temperature of the Earth would be about 33°C cooler, from an average of +15°C to -18°C.

Think of the greenhouse effect like a lid that’s half covering a pot on your stove.

Unfortunately, humans have been pumping enormous amounts of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere. Since the beginning of the industrial revolution, Dessler reports, we’ve put about 2,200 billion metric tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere. (A metric tonne is about 2,200 pounds.). Plus the other greenhouse gasses.

This has pushed Earth’s energy balance way out of equilibrium.

The increase in GHGs means the atmosphere is now absorbing more energy, causing the Earth to heat up as the planet tries to find a new equilibrium.

Earth’s average temperature has already warmed by about 1.1°C since the beginning of the industrial revolution. Dessler shows the energy imbalance is already large enough to keep the Earth warming until the 2040’s or 2050’s even if we take aggressive steps to reduce GHG emissions. And our GHGs emissions are still increasing.

We’ve moved the lid to fully cover the pot and we’ve clamped it down.

There’s a little chemistry and a little math in this part of the book, but Dessler explains it all very clearly. I found it really fascinating.

One thing that struck me is how small differences can have a huge impact. For example, CO2 makes up just 0.042% or 420 parts per million of the Earth’s atmosphere, but because it absorbs so much heat from the planet’s surface, it plays an outsized role in our climate.

Similarly, an increase of just 1.1°C is already having significant impacts on the climate and on human, animal and plant life. Staying within the UN’s target of 1.5°C is going to be a herculean task, and even 2.0°C is going to be a huge challenge.

Impacts, Policies and Politics

Dessler’s focus in the second half of the book is to teach us how scientists and policymakers try to forecast how much GHG we will emit in future, and what to do about it. Here we shift into an economic and political analysis of the climate change problem.

The framework Dessler uses is something called the IPAT model. It’s a simple equation that looks like this:

I = P × A × T

where:

- I is the impact of human activity on climate, in this case GHG emissions

- P is population

- A is affluence, measured in gross domestic product (GDP) per person

- T stands for technology and represents how efficiently (or not) we consume energy

Essentially what this model says is that our carbon emissions depend on population (more people means more emissions), our affluence (we emit more as we consume more), and technology (emissions depend on how efficiently we use energy).

T is broken down into two factors:

T = EI × CI

where:

- EI is energy intensity, a measure of how much energy it takes to produce one dollar of GDP.

- CI is carbon intensity, the amount of carbon we emit for each unit (joule) of energy we consume.

Dessler reports that both EI and CI are declining today. This is good: we’re using relatively less energy to produce the goods and service we consume, and we’re emitting less carbon per unit of energy we use. However, population and affluence are increasing faster than energy intensity and carbon intensity are declining. Bottom line: Earth is heating up.

Putting all this together Dessler walks through the steps for projecting climate impacts.

First, the IPAT model predicts GHG emissions. Depending on what assumptions you make for population growth, carbon intensity, etc., you get different predictions. Today, most predictions are based on Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). SSPs are a set of scenarios that modelers are using to project the socioeconomic and climate impacts of alternative climate policies. When you read news reports about dire climate assessments coming from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), they’re based on these SSP scenarios.

Next, the projection for GHG emissions gets fed into climate models that predict how much additional GHGs will stay in the atmosphere and what the impacts will be on temperature, precipitation, sea level rise and other important climate indicators.

Now we have to figure out what to do.

Dessler reviews four ways to address climate change.

- Adapting to changes that are already happening, like reinforcing sea walls. Some of this is already underway. Much more will be needed.

- Mitigation or reducing our emissions, mainly by reducing the carbon intensity component of the IPAT model. This is all about the switch to renewables and decarbonizing our economy.

- Solar radiation management. Mitigations may not be enough so Dessler thinks we might need to reduce the amount of solar radiation actually reaching the Earth’s surface. One approach could be seeding the clouds with more aerosols to increase cloud cover and reflect more sunlight.

- Carbon removal (CR), basically sucking CO2 out of the atmosphere. The technology to do this doesn’t yet exist at the scale we need, but increasingly the IPCC and other policymaking organization are factoring carbon removal into their models. They’re relying on non-existent technology to remove enough carbon from the atmosphere to meet policy goals.

Dessler strongly advocates putting a price on carbon, either through a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions. I agree with him, but carbon pricing has proven to be extremely unpopular in the US. Given the polarization here, it’s a political non-starter. The Biden Administration took a different approach with the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), its signature piece of climate legislation. The IRA provides billions in incentives and funding to stimulate climate action like switching to renewables. I hope it works.

Dessler concludes the book with a review of the history of climate science and climate politics. He summarizes the increasingly strong warnings coming every five years from IPCC Assessment Reports. And he dissects opposition from the fossil fuel industry to any attempts to wean ourselves off coal, oil and natural gas.

He notes that opponents are following the “tobacco strategy” – the strategy used by the tobacco industry to oppose anti-smoking campaigns in the 1960’s and 70’s. Tobacco companies attempted to throw doubt on the scientific evidence for the dangers of cigarette smoking, claimed more research was needed, found (or paid) a few contrarian spokespersons. The same playbook was used to oppose actions on acid rain and protecting the ozone layer. Today the fossil fuel industry is running the identical playbook on climate change.

But the science of climate change is solid.

“There is no question that, when you add a greenhouse gas to the atmosphere, the planet will warm. There is no question that human activities are increasing the amount of greenhouse gas in our atmosphere. There is no question that the Earth is currently warming, and it is warming about as much as you would expect from the addition of greenhouse gasses. This science is not new – much of it is a century or more old and has stood the test of time.” [p. 257]

It’s true that projections of future climate change, the impacts on humanity and on the planet, and the costs of responding are all somewhat less certain. But Dessler argues that we must act, and act now, even in the face of this uncertainty, because the costs of not acting are likely to be catastrophic.

Unsolicited Feedback

I learned so much from Introduction to Modern Climate Change, especially the first half of the book explaining how Earth’s climate works. This is the most technical book on climate change I’ve read so far. I won’t claim to have fully grasped everything in the book, and I certainly don’t understand it well enough yet to explain it all clearly, but I now have a much better grounding in the science of climate and climate change.

In my previous post, I reviewed Mark Maslin’s Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction. It might be a little unfair to compare it with Introduction to Modern Climate Change. After all Maslin’s book is aimed at a general audience while Dessler’s is a college textbook and about 100 pages longer. Still they’re both pitched at an introductory level.

So which one is better?

The two books overlap a great deal, especially on the impacts of climate change and the policies for addressing it. The overall organization of both books is similar too.

Maslin’s book is shorter so it’s a quicker read, and as I said in my review, he covers an impressive amount of ground in such a short book. He spends is a little more time on the politics of climate change than Dessler, and he’s more in-your-face in his rebuttals of climate change deniers. Dessler writes in a more neutral tone, although his opinions still come through loud and clear.

The biggest difference is that Introduction to Modern Climate Change goes way deeper into the science of climate and that’s what I was really looking for. It’s a longer, more challenging book, but well worth the effort.

Thanks for reading.

* * *

Please click here for more posts on climate change.

If you liked this post, please follow Unsolicited Feedback.

Related Links

Additional Resources: a set of links to additional resources for each chapter of the book provided by Prof. Dessler on his personal web site.

Skeptical Science: a website dedicated to explaining climate science and rebutting climate misinformation.

The Kaya Identity: a form of the IPAT model specific to CO2 emissions.

The Economic Tipping Point for Energy Transition

Video interview with Andrew Dessler at Texas A&M University’s Innovation Forward conference, November 25, 2024.

Oil and Gas Companies Are Trying to Rig the Marketplace

Guest essay by Andrew Dessler in The New York Times, June 1, 2024.

An explanation of how renewable energy saves you money.

Post on Andrew Dessler’s substack, The Climate Brink, 27 Jan 2025.

Discover more from Unsolicited Feedback

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Nonfiction November 2023 Week 1: Your Year in Nonfiction | Unsolicited Feedback

Pingback: 2023 Reading Wrap-Up | Unsolicited Feedback

Pingback: Our Fragile Moment | Unsolicited Feedback

Pingback: Hot Mess | Unsolicited Feedback