The centuries-long rivalry between Oxford and Cambridge Universities isn’t limited to just boat races and rugby matches. Both esteemed universities have recently published updated versions of their introductory books on climate change.

I’ve read and reviewed a number of books about climate change, but I wanted to find one that presents a comprehensive introduction to the problem. Both these books seem like good candidates.

I’ll review the entry from Oxford University Press first. It’s called Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction by Mark Maslin. In my next post I’ll look at the Cambridge University Press offering, Introduction to Modern Climate Change by Andrew E. Dressler.

I’ll announce the winner at the end.

Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction, 4th Edition

By Mark Maslin

Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2021

Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction is a slim pocket-sized book that packs a wealth of information into just 156 pages. It’s written by Mark Maslin, a Professor of Earth System Science at University College London. Incidentally, there are over 700 of these Very Short Introduction books produced for a general audience by Oxford University Press.

Maslin covers climate change from a wide variety of angles: its geological history, modern anthropogenic (human-caused) origins, impacts, possible solutions, and surrounding politics.

History of Climate Change

The book begins with a look at the history of climate change. Maslin explains that climate change has been a constant feature of Earth’s geological history, mostly due to changes in Earth’s orbit around the Sun. For most of the past two million years, the Earth has been significantly colder that it is today. We’re presently in a warmer interglacial period called the Holocene that began around 10,000 years ago.

Something I didn’t know: we’re actually overdue for another ice age but humans started cutting down forests about 7,000 years ago for agriculture, cities and roads. Those early land use changes seem to have increased the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere by just enough to delay the onset of the next ice age. Humans been impacting Earth’s climate for a long time it seems.

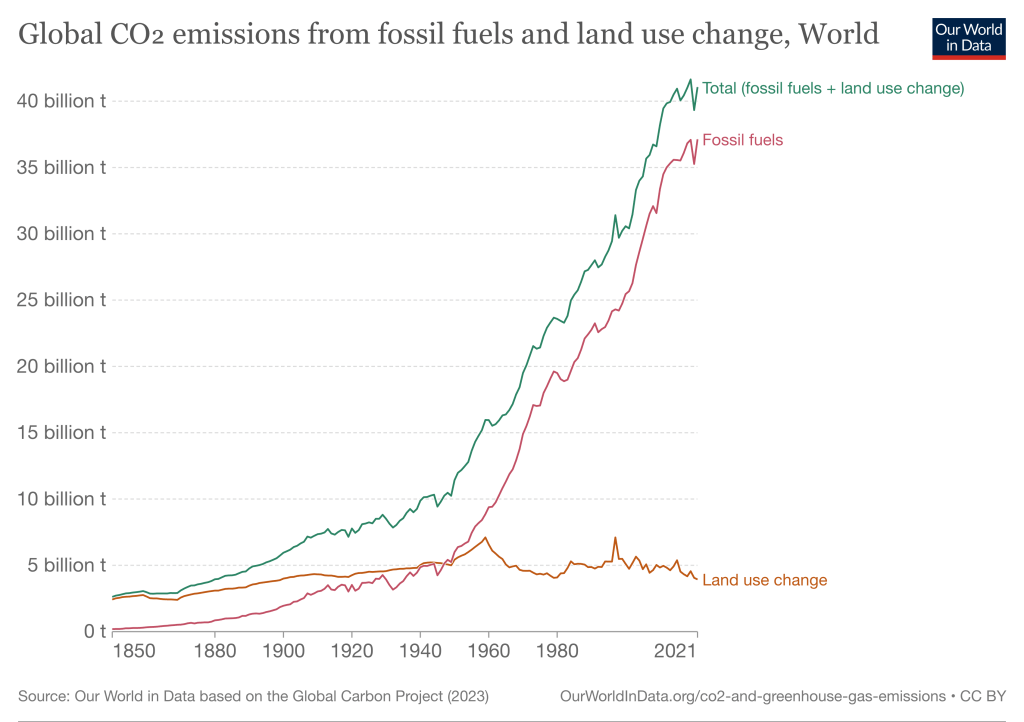

Today, land use changes still account for 10-15% of CO2 emissions. The other 85% comes from burning fossil fuels which started about 200 years ago with the Industrial Revolution.

Burning fossil fuels is the real problem because it’s increasing atmospheric CO2, and global temperatures, faster than at any time in Earth’s history.

Maslin presents an array of scientific evidence for anthropogenic climate change and makes a valiant attempt to directly refute some of the counterarguments of climate change deniers. I say “attempt” because at this point I doubt anyone who still questions the origins of climate change can be swayed by evidence.

I was disappointed by the chapter on climate models. I didn’t get a clear sense of how these models worked. However, the discussion of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) was helpful. SSPs are a set of scenarios that modelers are using to project the socioeconomic and climate impacts of alternative climate policies. When you read news reports about dire climate assessments coming from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), they’re based on these SSP scenarios.

Impacts and Politics of Climate Change

Maslin details the predicted impacts of climate change including extreme heat, drought, wildfires, floods, storms, sea level rise, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, losses to agriculture, and threats to human health. It’s unrelentingly grim, but we shouldn’t fool ourselves about how serious the consequences of inaction will be.

Then there’s a set of what Maslin calls climate change “surprises.” None of them good. These scenarios are less certain but could occur if climate change reaches certain tipping points. They include massive release of methane from the thawing of the Arctic permafrost or a dieback of the Amazon rainforest.

One subtle but important impact that Maslin highlights is the increasing unpredictability of the weather. Earth’s rapidly warming climate is destabilizing weather patterns, like seasonal monsoons, that humans have depended on for thousands of years. Our very survival often rests on our ability to predict the weather – something that is now becoming much more difficult.

The chapter on the politics of climate change presents a useful chronology of the various treaties and conferences aimed at securing international agreements to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Progress has been infuriatingly slow. Even today, all the commitments that various nations, including the US, have made are voluntary and unenforceable.

It’s good they’re still talking and at least making the right noises, I suppose. But it’s dismaying to realize how fragile diplomatic progress has been. Trump withdrew from the 2015 Paris Agreement, but fortunately Biden rejoined.

It seems like we’re just one bad election away from the whole thing unravelling.

Adaptations and Mitigations

The book finishes up with a comprehensive inventory of climate change solutions. They’re divided into two categories: adaptation and mitigation.

Adaptation to climate change includes physical measures like reenforcing sea walls and restoring wetlands, and social adaptations like better emergency preparedness for extreme climate events and securing people’s access to food and water.

“In many ways the most important adaptation to climate change is good governance, so that policies can be formulated and enacted to protect the most vulnerable people in society.” [p. 125]

Mitigation refers to all the measures we must take to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This includes switching to clean energy, carbon taxes and trading, reforestation and rewilding, carbon capture and storage, and more outlandish ideas like geoengineering. Maslin has assembled an impressive list of these solutions. We’re probably going to need all of them if we hope to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

I like that Maslin makes it clear we must address climate change in a just and equitable way, enabling billions of people in developing countries to achieve the better lives they aspire to. As he says, tackling climate change fully and fairly will require the combined efforts of individuals, communities, corporations, local and national governments, and international institutions.

Unsolicited Feedback

I found some of the more technical sections of Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction to be less clear than I would have liked, and some of the diagrams left me scratching my head. Maybe the very short nature of this book doesn’t leave enough space for more detailed explanations.

I got confused by the statistics about how much greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions we’re pumping into the atmosphere. In a couple of places, Maslin says we’re adding 40 billion metric tonnes per year of CO2 into the air. (A metric tonne is 1000 kilograms or about 2200 pounds.) That figure matches up with this graph of global C02 emissions from fossil fuels and land use changes from Our World in Data.

Elsewhere in the book he says we’re putting 11 billion metric tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere each year. I’m not sure what exactly this means. I presume it refers only to the weight of the carbon atoms in CO2 or CH4 (methane), but this is never stated clearly. And I also don’t understand why the book sometimes refers to carbon emissions, sometimes to carbon dioxide emissions, and sometimes to greenhouse gasses generally. It’s very confusing.

To be fair to Maslin, there are many different statistics thrown around in the climate change discussions. For example, this graph of global greenhouse gas emissions, also from Our World in Data, shows that we’re emitting about 50 billion tonnes of GHGs including carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide per year. This is the number Bill Gates used in his book How to Avoid a Climate Disaster. Writers do need to be very clear about the numbers they’re using and what they mean.

On the other hand, the chapters dealing with climate solutions and politics were really good.

Overall, Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction gives an impressively broad survey of the climate change problem for such a brief book. I think the book provides a good balance of scientific, socioeconomic and political material. It did leave me wanting to read more for a deeper understanding of some of the technical details.

Prof. Maslin also does honorable public service by tackling climate change deniers head on.

Thanks for reading.

* * *

Please click here for more posts on climate change.

If you liked this review and would like to get notified of more Unsolicited Feedback, please follow this blog by entering your email address above.

Related Links

Our World in Data is a great source for more excellent graphs about climate change and other topics.

Project Drawdown has a comprehensive index of climate solutions.

The triple inequality of the “global” climate problem, a post by historian Adam Tooze, highlights recent research showing that climate change will most heavily impact those who have contributed least to the problem and are least able to pay for solutions.

Discover more from Unsolicited Feedback

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Introduction to Modern Climate Change | Unsolicited Feedback