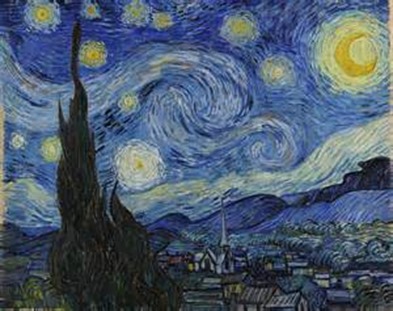

If Vincent Van Gough were alive today he couldn’t possibly paint The Starry Night.

That’s because our modern obsession with more and brighter lighting has obliterated the stars and threatens to banish night itself. This is one of many poignant observations you’ll find in Paul Bogard’s excellent book The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light.

The night sky Van Gough saw in 1889 when he looked out the window of his asylum in St. Remy in southern France was a sky filled with stars of different colors and sizes, a swirling Milky Way and a moon that seemed to pulse with light.

That sky doesn’t exist anymore.

Instead, Bogard tells us, we have sky glow, a dull orange-pink light spreading up from the horizon that looks like it might be the last vestige of sunset except this sun never sets. It comes from streetlights, and parking lot flood lights and building security lights that don’t turn off until the sun rises again. And unless you travel into the countryside, and increasingly into the remotest parts of the country, sky glow masks out all but the brightest stars.

The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light

By Paul Bogard

Back Bay Books/Little Brown & Co., New York, 2013

The End of Night is Paul Bogard’s poetically written journey into, yes, the heart of darkness.

Bogard takes us from the most brilliantly lit spot on Earth – the Las Vegas strip – to some of the darkest remaining places in the United States. Along the way he makes a compelling case that by lighting up the night we’re losing more than just the stars; we’re losing a connection to nature, and to our own natural selves.

He’s not saying artificial light is inherently bad. In fact it brings undeniable benefits by allowing us to extend our work and social lives into the hours of darkness. But we’ve over-done it and done it badly.

Light pollution is defined by the International Dark-Sky Association (there really is such an association) as,

Any adverse effect of artificial light including sky glow, glare, light trespass, light clutter, decreased visibility at night and energy waste. [p. 25]

It’s now so bad, Bogard claims, that 99% of people in the continental United States and Western Europe can no longer see a truly dark sky, that is, a sky with a class 1 rating on the Bortle scale of night sky brightness. Take a look the World Atlas of the Artificial Night Sky Brightness for a glimpse of how lit up your night sky is.

Ironically, while safety is usually the main reason for increased night time lighting, Bogard cites plenty of experts, including the US Department of Justice, who say there’s no correlation between brighter lighting and reduced crime. In fact, modern “cobra-headed” streetlights may actually reduce safety because you can’t see through their glaring pools of light to the mugger (or the zombie!) lurking in the darkness beyond.

But the most important parts of Bogard’s book tell how the loss of darkness is also a loss of vital human experience. I’m not doing the book justice here, but the essence is this: Daylight is a time filled with responsibilities and obligations. To fulfill them we don masks and play roles: worker, manager, doctor, teacher, leader. But at night we take off our masks and experience our true selves. We experience the mysteries, the fears, and the sadness of our lives and of the world more fully in the ambiguity of darkness. Of course, we fear the dark. It’s related to our fear of death. But both are unavoidable and it’s important to face them and to know them. So darkness is not just an opportunity, it’s a necessary part of human experience.

In ways we have long understood, and in others we are just beginning to understand, night’s natural darkness has always been invaluable for our health and the health of the natural world, and every living creature suffers from its loss. [p. 8]

Bogard walks a delicate balance between melancholy over the irretrievable loss of natural darkness, and hopefulness that we can still act to restore something of the night sky.

It’s too late to completely revert to the dimly lit nights Van Gough would have been familiar with. Yet Bogard suggests there are two things we can do.

First, we can actually think about lighting. Carefully plan how we want our communities to be lit. Produce the right amount of light, directed in the right locations, and illuminated only for as long as needed. For example, why couldn’t we turn off street lights after midnight and use motion sensors to turn them on again when needed? As they’re doing in parts of Paris, we could mount lights closer to the ground, say no more than 15 feet, and use fixtures with recessed bulbs to reduce glare and light trespass.

A simple change to building codes would go a long way to solving light pollution One of the experts in the book suggest that codes just need to say, “all exterior light will be directed only on the premises to be illuminated.” [p. 229] That’s it. This means exterior lighting could not be directed or spill into a neighbor’s bedroom, or their backyard, not onto the street, and not into the sky. Over time, as new development occurs and old buildings are brought up to code, light pollution would gradually fade away.

The second thing we must do is preserve the few remaining areas of true darkness.

This is where our national parks come in. It turns out an unforeseen benefit of the national park systems in the US, Canada, and other places is that they preserve local pockets of darkness. Bogard’s descriptions of night time viewings at Death Valley, Bryce Canyon and Natural Bridges Monument make me want to load up my backpack and head off to see them soon in case light pollution invades even these last strongholds of darkness.

Guided night sky viewings are an increasingly popular attraction at our national parks. Perhaps that’s because most of us live in light-washed cities where we go months or years without noticing or even seeing the stars.

How upside down this world where what was once a most common human experience has become most rare. Where a child might grow into adulthood without ever having seen the Milky Way and never feel as though lifted from Earth into surrounding stars. [p. 271]

Unsolicited Feedback

At first I thought The End of Night was going to be just another depressing read about how we humans are screwing up the environment. Again. And if that’s all the book was about, it wouldn’t be half as interesting.

But Bogard shows not just the damage that too much artificial light is causing, he also suggests some relatively simple, concrete steps to mitigate the problem.

Most of all, he presents a moving case for the value of darkness itself.

It’s a terrific, beautifully written book. Read it, and then, wherever you are, turn off the lights and look up.

Update (June 20, 2023): Paul Bogard writes in The New York Times that persistent smoke from forest fires caused by climate change is creating a permanent haze in the air. Not only are we losing the night sky, we’re losing the blue skies of daytime too. Here’s the link: We’re Watching the Sky as We Know It Disappear.

Related Links

If you’re interested in finding out more about the impact of light pollution on the night sky, and what to do about it, here are some useful links:

- International Dark-Sky Association: http://darksky.org/

- National Park Service, Night Skies page: http://www.nature.nps.gov/night/

- Réserve international de ciel étoilé du Mont-Mégantic (Mont Megantic International Starry Sky Reserve): http://ricemm.org/ (in French)

- Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Light Pollution Abatement page: http://www.rasc.ca/lpa

- The StarLight Initiative: http://www.starlight2007.net/

- World Atlas of the Artificial Night Sky Brightness: http://www.lightpollution.it/worldatlas/pages/fig1.htm

Looks like a good book to read!

LikeLike